It’s been a little bit since I touched on this series while we had some other items going on in preparation for Fort Alice releasing, so for those of you that don’t remember the last post, you can check it out here. This series goes further into the ins and outs of what it’s like working on and around a railway in the world of 1879, to help both Game Masters and Players to flesh out the world and their role playing in games.

We’ve gone over passenger trains and the jobs and terminology of trains in the previous posts, so for this one I’d like to get a little bit further into freight trains. Despite how prevalent passenger trains have become, moving large amounts of freight long distances is the primary purpose railways got their start. Adventurers are far more likely than the general public to have to deal with freight trains. They could be hired on as additional security for a train with sensitive cargo, or get pulled in on the opposite side and be hired on to rob something important off of a train. If they really make it big on an adventure, they may also need to hire on a freight car or two in order to haul back their gains in order to profit. As usual, there’s a lot I can talk about here, so let’s dive on in.

First up, a basic review of the most common types of rolling stock being dealt with. Statistics for most of these are covered in the books; this is primarily intended to give some additional insight into the construction and how they’re used in operation.

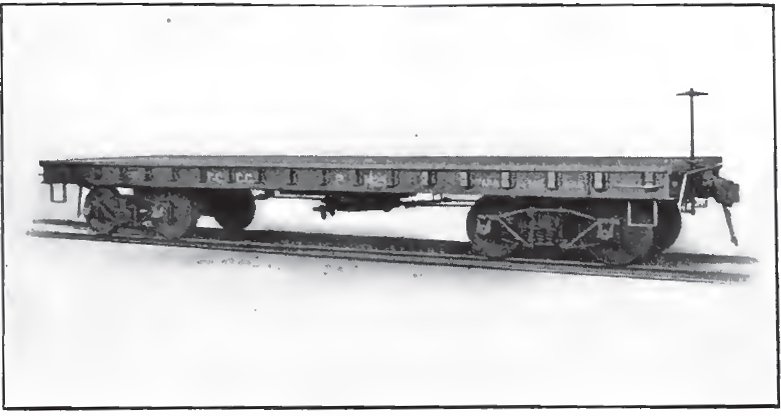

Flatcars: As absolutely basic as it gets, freight flat cars consist of the wheel base that rides on the rails, related suspension to handle the potentially heavy and uneven load over bumps and curves, and a rectangular flat bed of heavy construction for it to be mounted to. This is generally the basis for other types of freight rolling stock, with additional build up on top to suit the particular need. Most standard gauge flat beds at this point in time will use bogie trucks for the wheel base to handle the weight as well as curves in the rail line. In the Union/Confederacy, most rolling stock has independent braking systems that brakeman can run along the train to deploy, such as the one in our example image below (notice the shaft and crank wheel sticking up on the right). In British railways, rolling stock generally do not have independent brakes; this makes them simpler to construct and operate since they can reduce the crew costs, but also means they’re entirely reliant upon the engine and brake van to provide stopping power.

Box Cars: Exact terminology for this type of rolling stock will vary depending upon the exact type of cargo and related modifications for that cargo; for example, livestock cars will often have open slotted sides for ventilation for the animals (as well as their smell). The basic principle remains the same; it’s a flatcar base with a box built on top. To keep it simple, if it’s got a roof, it’s generally referred to as a type of box car; if there is no roof, then it’s generally referred to as a type of flatcar. If there are brakes, the primary controls are usually mounted on top so that brakemen can jump along the top of the train to deploy brakes quickly without having to climb down to each piece of rolling stock, with a secondary linked control down low to manage the truck from the ground when the train is not in motion. The access doors are on the side, and will usually slide on tracks to open/close (some older models will still have a hinged door, but these are a rarity). There may or may not be a hatch on top of the car to get inside, but generally there is no intention for anyone to be able to go into or out of a box car once it’s sealed up and in motion. Be sure to play up this difficulty with your players in a scene, and emphasize the importance of skills like Climbing and Athletics if they’re trying to scale along the side of the car or parkour their way in or out.

Tanker Cars: These will generally be referred to by whatever type of fluid they’re meant to carry; milk, water, oil, so on and so forth. They generally consist of a flat car with a cylindrical tank on top, and related mounting brackets to keep the tank firmly secured. As fluids slosh around when they are transported, special consideration has to go into how they are carried. Many tanker cars build the tanks with separator walls inside to break up how much room the fluid has to move around; solid walls that divide the tank up into smaller sections are bulkheads, and bulkheads with holes in them to still allow the fluid to flow between sections are called baffles. This is not possible for all fluids; for example, most tanks for food products do not use bulkheads or baffles due to the greater difficulty of cleaning and sanitizing them. As such, these types of tanks are generally smaller and kept on cars with fixed wheel bases rather than bogies, limiting their side-to-side movement as well as how much weight over all is allowed to slosh around in the tank. Too much weight sloshing can not only run the risk of tipping the car over, but makes the train more difficult to handle in braking.

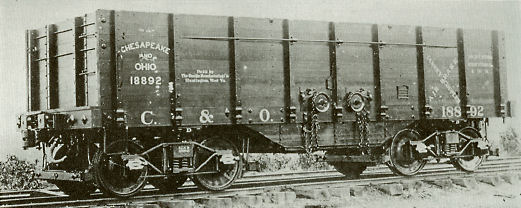

Hopper Cars: Often used as a general term for any open top car with sides, there’s a bit of a split and a misnomer for the types. True hopper cars will have sloped sides moving down to a chute at the bottom. These are used for carrying dry, piecemeal goods like coal, crushed stone, dirt, and sand, and dumping them out the chute when they are delivered. Often the term is also used to refer to open top cars with flat sides, which are generally used for goods that are easier to load and unload from the top but which could still benefit from more protection and containment on the sides than a flatcar would provide, and this version may or may not have a chute in the bottom. Occasionally the flat walled variety will also be used for piecemeal goods and will rely on manual shoveling to completely empty them out.

From a logistics standpoint, most freight trains will run secondary priority to passenger service, since most goods aren’t going to complain if they’re a few minutes late getting to their destination. As such, anyone looking to get onto a train in a less than legitimate way are more likely to catch a freight train than a passenger train. Freight trains are inspected for stowaways, though often only when leaving and arriving at a station unless there is a long delay or a specific call for additional security. Freight trains are considered to be property of the railway they’re running on, and punishments for being caught trespassing range from fines to prison time, potentially worse if other crimes are observed or suspected. Since the AGR is owned by the military, inspections are more common and punishments fall to military police standards rather than civilian, so actually hitching a ride is less frequent there. More there common is to simply smuggle goods and messages on a train and rely on someone else to pick them up on the other end; a crate of illicit goods is just as likely to go unnoticed as any other of the several thousand crates and inspector sees every day, but a person found carrying them will get immediate attention.

Inspections are a different story once a train is in motion; since the train is not designed for people to move between cars, unless a car has people positioned with it when the train gets moving, the cars themselves and the goods on them are not going to be guarded. This is not to say that they won’t be watched, however. Both British brake vans and Union/Confederate cabooses have sections on the side and top to allow crews inside to watch along the length of the sides of the train, and often one to watch from the top as well. Primarily, this is for them to watch for hot boxes, or when the bearings on the wheels of a piece of rolling stock run hot and start smoking, but it also allows them to watch for anyone trying to board or move along the train. In the event of such an emergency, the crew is able to signal the engineer to stop the train so the threat can be dealt with. As such, the scenes you often seen in movies and television where would-be train robbers can simply hop on a horse to move along side of the train (or worse, jumping on from the rear where all the crew is located) and spend as much time as they like loading themselves and equipment are not realistic. That’s not to say it’s impossible, but the crew in the crew would need to be dealt with before the engineer could be signaled, or they’d need to move fast enough and stealthily enough to avoid being seen, or use some sort of magical assistance to avoid detection. Given that a lot of trains are mixed traffic, carrying both passengers and freight (especially in the Gruv), often the easiest solution to rob one is to board legitimately and then sneak away to get at whatever goods you’re trying to find. These are problems that players should be encouraged to think about creatively in this situation, whether they’re using techniques to board a train or protecting one from being boarded.

I’m trying to keep these posts a bit shorter than the previous ones, so I think it’s probably best to wrap this one up here. If there are other questions you’ve got on the subject for how trains might be used in gameplay, or if you’ve got ideas or stories about how you’ve used them in your own game, please share with us on Discord. We’ll see you next week!