1879: Pictorial Sources for the Omnibus

In the course of describing London and other cities for the 1879 sourcebooks, I’ve come across a lot of reference images. Photography was in widespread use by the late 19th century. Painters were still major art celebrities, with the unveiling of a new painting by a recognized master being a social event.

Getting across town has always been something of a chore. Anyone who rides the bus or the subway or the L now has an experience much the same as that of 140 years previously. Let’s have a look at some of the images that have inspired 1879‘s omnibus descriptions. Players and GMs might find all sorts of inspiration in these.

From 1859, here’s William Maw Egley’s most well known work, Omnibus Life in London. Egley positioned the view at the front of the bus, looking rearward to the back door and a view outside of Westbourne Grove, near Egley’s home at Hereford Road. While this is in Sunderland, far to the north of London, on the coast up by Newcastle-on-Tyne, the dress and the business of the travelers wouldn’t have been that much different from London’s West End.

It’s worth noting that this is a horse drawn omnibus, with a curved ceiling that says there’s no topside seating. and advertising where there really ought to be windows. This omnibus would have been stuffy, stinky, and damp, with straw scattered on the floor to soak up whatever the passengers tracked in, churned into mucky slime by the end of the first run of the day. Of course it’s crowded. The cad, later known as the conductor, is quite sure he can fit one more couple if people will just scoot down a little. Never mind that the fashions of the day take up as much room as the people themselves. With each passenger paying a penny a mile, the more the cad is able to pack in, the more the run makes for himself and the driver. Now imagine trying to shoehorn a troll into this.

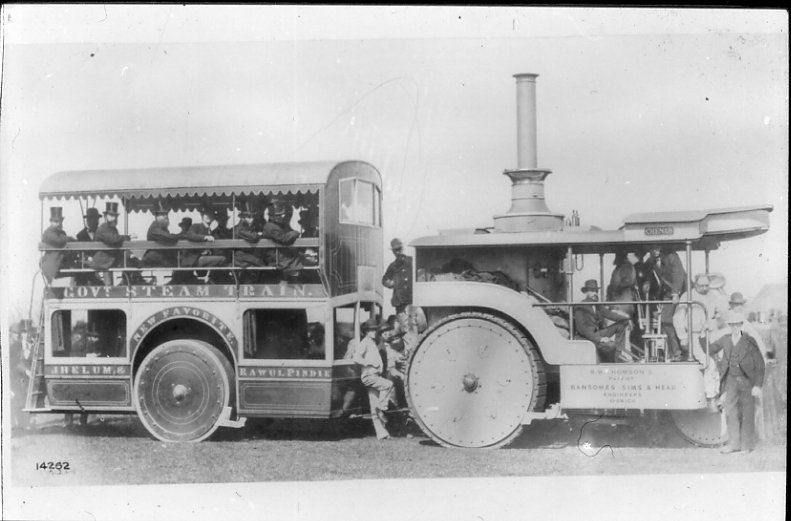

No, our friend the troll is going to have to ride on the knifeboard. That’s the seat that runs fore to aft, facing out to the sides, or a pair of seats along the outer rail, facing each other, up on top of the bus. In either configuration, the passengers on the knifeboard are exposed to the elements and in a dangerous position should the top-heavy coach tip over. In this 1845 photo of an early steam bus, the tractor drawing it is the same size as the coach, but at least the knifeboard passengers have a solid front between them and the smokestack.

Here’s a 1902 Thornycraft steam bus, usable in our game world given the acceleration of technology. It’s got proper forward facing seats up top, but note the lack of shelter from the elements other than a perfunctory tarp to keep the sun and the worst of the rain off. Anything blowing in from the sides went straight across the passengers, including smoke from the forward stack in a downdraft.

Running in the borough of Hammersmith, as proudly proclaimed on the side, our troll would pay an extra penny a mile due to their size and climb the narrow, steep ladder to the knifeboard. The cad would probably ask a few non troll passengers to move to the other side to keep the vehicle balanced. No, women didn’t normally ride on the knifeboard. Climbing that ladder would allow men to see up their skirts. Women in trousers, now, that’s another story, and that’s fraught with its own issues, a bit more than we want to get into here.

Let’s move on to a side view of the interior, in a less crowded bus.

Here, in The Bayswater Omnibus, George William Joy has depicted a more modern conveyance – the painting was done in 1895 – with slat flooring for proper drainage, larger windows, and a bit more room in general. The fashions of the day still take up perhaps a bit more space than those of the modern era, which has to be accounted for when determining the number of passengers one can pack in without violating social mores.

We’ll close out with this rear-boarding Midland steam omnibus. It’s got solid rubber tyres, a later invention that gave a much smoother ride and were nowhere near as hard on the cobbles as the iron tyres of earlier wagons and buses. It also has a considerable amount of its length given over to the engine and cab, which later buses would shrink in the interest of giving over more space to paying passengers.

Note that, like all the other omnibuses we’ve seen, its passenger capacity is only half that of a modern city bus, if that. A party in a hurry might do better to hire a hackney cab, rather than either splitting the party between two or more omnibuses or having to wait for one with enough room for everyone.

In short, the late nineteenth century omnibus was crowded, stinky, uncomfortable, and a bit pricey, but it beat walking. Much like today.