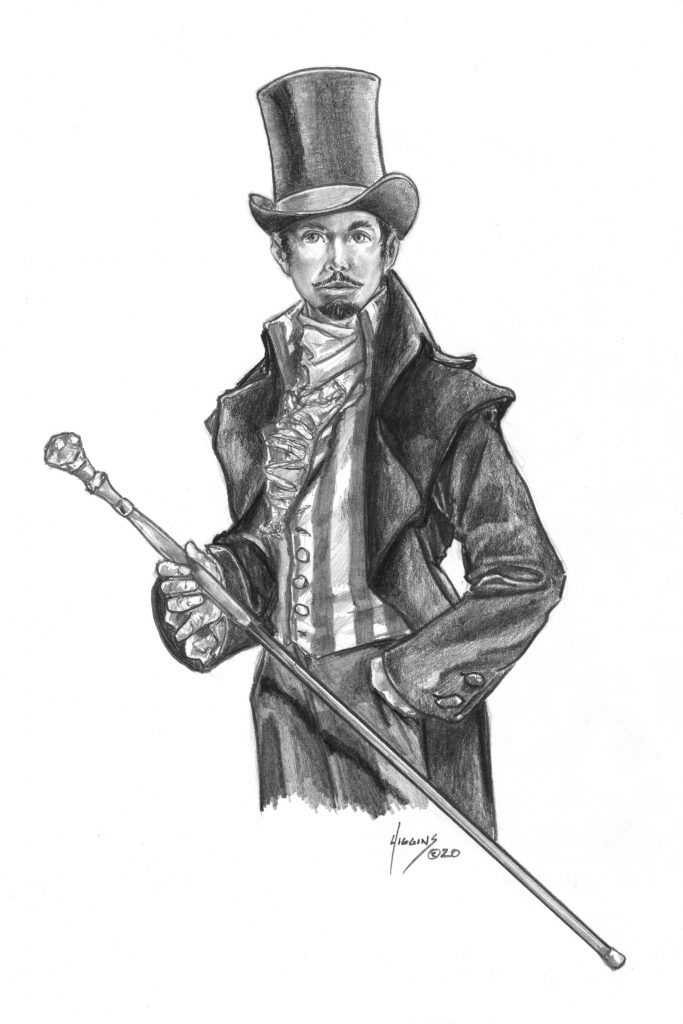

Dillon Tipton, Senior Lovelace, Flash Wizard Byron

Growing up in Atlanta, Georgia, in the postwar recession and recovery, Dillon knew he didn’t belong in a dress, or playing with dolls, or learning to keep a house. He was a boy, whatever his body and his parents said. With the Confederacy rebuilding its economy by keeping many of its factory workers turning out the same guns, ammunition, and airships as they had during the War, and selling them to other nations, Atlanta offered plenty of opportunity for a young person who could slip away from their working-class family, dressed in boys’ clothes stolen off a clothesline eight blocks away in a more well off neighbourhood, parents too busy trying to make a living to notice that their child wasn’t in school. The night he came home with his hair cut short, Jack and Donna made a fuss about it, but he pulled out a dollar bill he’d earned at the machinist’s shop two streets over and told them it was a safety measure. Those were hard times, in a harder world, when a child who could help buy groceries did. He got away with it, as well as insisting he wasn’t Maude Marie, but Dillon, after he took his father over to meet Mr. Hubert, who laughed and said he didn’t allow anyone in the shop with long hair, and Dillon was a hard worker, then slipped Dillon a wink when his father wasn’t looking.

Mr. Hubert made parts for Engines, and that introduced Dillon to the people who built and maintained them, and through them the people who coded for them. Here was order, here was clockwork perfection, predictability, the ability to make a thing be simply because you said so. If you declared a variable, the Engine accepted whatever value you gave it, no questions. A clever young person with the right mindset could learn all sorts of things from these people, and a new Byron was born.

But it couldn’t last. Dillon was growing up, with all that involved, and the identity he’d built started to slip away. Through the telegraph network, he’d found a few other people like himself. Dr. James Barry was ten years gone, but his name had cachet, and that led to the Barry Society, and to information about the world’s accelerated developments in medicine and prosthetics. That was going to take serious money, not the kind he could earn with his parents looking over his shoulder. His mother had found her old kitchen book when she was packing to move back in with her mother, Dillon’s father having become abusive after five years of hard drinking to kill the pain where he injured his back at the mill. Jack was becoming abusive toward Dillon as well, and starting to make threats of specific violence to teach him a specific lesson that Dillon didn’t even want to put words to. In the kitchen book had been a family photo, taken as a Christmas gift everyone could enjoy, the year before Dillon had stopped answering to a dead name. That brought up memories, and discussions that should have been long over, and tapdancing around questions his mother just was afraid to ask for fear of what the answer might be. Everyone tried to avoid each other and the family was crumbling.

Seeing the writing on the wall, Dillon built a new card deck, cried over it, and then slipped it into the queue at city hall with the morning train shipping data from the cargo depot. Maude Marie Clifford officially ceased to exist. Dillon Tipton took her place in the records, and while there was still a birth certificate on file, as Dillon’s parents had been well off enough to have a registered birth with a midwife present, nobody looked up the paper records unless there was a reason to question the Engine data. He packed what little he needed and could call his own into a cardboard suitcase and caught the third-class overnight to Mobile, where he wouldn’t meet anyone who had ever known Maude.

In 1865, an ammunition dump on the north side of Mobile, Alabama, exploded, killing three hundred people and levelling the area. This cleared land that factory owners swiftly bought up, leading to the late 1860s building boom and Mobile entering the 1870s as the fifth largest city in the Confederacy in terms of manufacturing, with an emphasis on the war trade. With such an influx of factory workers and skilled professionals, a Byron could slip in and get lost in the multitude. Finding a job was easy, only requiring a demonstration of coding skills good enough to get him a position at an accounting firm as a junior Engine developer, but not good enough to draw attention. With no degree, Peabody & Tyson Ltd. wouldn’t consider him for advancement anyway, leaving him just another faceless cardpuncher toiling away in the depths of the company. That suited Dillon just fine as a starting point.

Classes were the obvious next step. Being self-taught and mentored, Dillon had gaps in his knowledge of Engines and all the associated business and governmental functions. Getting into a decent college was just a matter of money, and with a steady paycheck from a reliable if boring company that was covered. Physical changes were next, though, and that was going to take more than a junior cardpuncher’s wage.

A city with a massive shipping industry, heavy manufacturing, and all the accounting and financial processing that goes along with that offers tremendous opportunities to those willing to bend a law or two. Mr. Smith, the Confederacy’s answer to London’s Mr. Fagin, does a land office business in environments like Mobile. Once the right connection had been made, and the first job done to establish bona fides, or mala fides as it were, a clever Byron could stay employed in a series of one-off jobs that all pay ready cash. Berthold’s extract, first created in 1849, wasn’t a perfect solution to Dillon’s physical issues, but a series of injections gave him a deeper voice, a redistributed muscle and fat profile, did away at least partially with some of the reminders of his physiognomy, and best of all, brought about the start of a beard and the end of the pasted-on moustache he’d so carefully applied each morning. The stuff was expensive, if you wanted it well prepared and of high purity, and obtained discreetly, although no man went looking for masculinity serums openly and admitted that he needed them, so a steady supply of cash was an absolute necessity. A beard took some patience and grooming to raise, even after a year of shots, but people quit looking so closely.

As far as physiognomy, there wasn’t a really satisfactory solution. However, a Byron knows Brassmen, and is a dab hand at Clockwork and hydraulics themselves. Dillon gained a bit of a reputation as a ladies’ man, whispered of among a select few as being one who could always rise to the occasion. College life was easy enough. Having a job provided a ready excuse for not going out drinking with the rest of the young men if he didn’t feel like it, but he had the money to go prowling the whorehouses, or to an illegal cockfight down in the poor (black) end of town if he needed to maintain his reputation as being slightly flash. Maintenance was an issue, the mechanisms were delicate and tended to get damaged with more enthusiastic use. That kept him busy in side work, which was rapidly turning into a second career.

After the Rabbit Hole opened, a whole new set of options opened for those with much larger sums available. A reputation for success with Mr. Smith and a willingness to take on the hard jobs covered the buy-in and a few weeks ostensibly in the country. Well, the Promethean’s lab was set up in a pre-War plantation house, those were cheap to buy these days. While this did away with the need for the prosthesis, and put Dillon past a milestone the size of the Chisholm Building in his restructuring of his identity, it pushed his maintenance costs much higher for the anti-rejection drugs. Dillon stepped up his game in both his day and night careers. This far in, better to risk arrest or being shot by a night guard than to run out of money for the upkeep.

Four years later, with a degree in mathematics and Engine programming, Dillon has advanced to a full developer’s position at the firm. His night work keeps him constantly busy, a hot Byron who’s on the leading edge of the technology being in high demand in certain circles. He’s garnered a certain amount of attention, including that of a few young ladies, and the flash life does have its charms. Between the two lives he’s built for himself, the respectable Engine programmer and the flash wizard Byron, he’s left with a choice he needs to make soon: which side of the street does he live on?

Character Sheet

See the PDF, and note the following.

- His Profession abilities are:

- +1 to Social Defense (reflected on the character sheet)

- Karma for any PER-only Test

- +1 to base Karma step (reflected on the character sheet)

- Codespeak: Byrons use a jargon that is incomprehensible to outsiders. By expressing themselves in Engine-related concepts and terms, they can converse in such a way that non-Byrons simply cannot understand them. Codespeak may be spoken or written, and forms an encryption that only another Byron (or a Lovelace, with an Engine Programming Test at -2 Steps) can decrypt.

- The money on his character sheet is what Mr. Tipton can legitimately claim. He can make an Engine Programming Test against the number of hundreds of pounds he wishes to acquire, whether by withdrawing from his own hidden accounts, siphoning from idle funds elsewhere, or interception of funds in transit. On a success, he gains that amount of funds. Each extra Success can be used to either gain another 10% beyond his goal, or to offset one Step of penalty from the next time he tries this trick. Moving that kind of money roils the waters, you see, and you need to let things settle before you do it again. Every time Mr. Tipton does this inside of a month, he takes a -2 Step penalty to the Test, cumulative, so -4 Steps for the third try inside a month, and at -6 Steps for the fourth try you might as well not bother. A Critical Failure closes off the source of the funds, and the money sought is lost to asset forfeiture.